Directors' Cuts Won't Save You

Watching a director’s cut of a film you’ve previously seen can be a fascinating experience. It can show you just how substantial an impact even the slightest bit of editing can have on a project.

Directors’ cuts are a unique kind of second chance—an opportunity for audiences to revisit a story they already know, but can return to with the knowledge that the experience they’re settling in for more closely aligns with what the narrative’s creator initially wanted to bring to the screen. At the same time, however, directors’ cuts are also studios’ blatant attempts at milking as much money out of a movie as they can by convincing people that the new release is something they need to see.

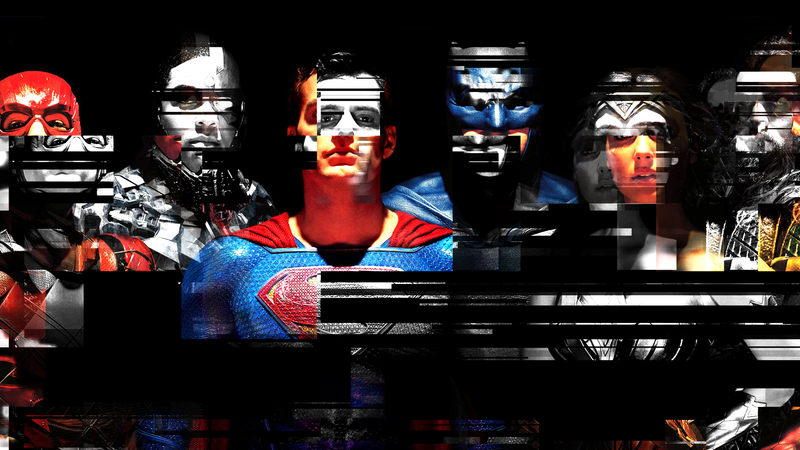

The onus has always fallen on the public to make the call whether a director’s cut is worth the financial ask, and studios have done their damnedest—with varying degrees of success—to make convincing arguments as to why we should spend our hard-earned dollars on them. But lately, there’s been a…fascinating, if baffling, uptick in people clamoring for directors’ cuts of genre films whose initial cinematic releases were met with less-than-stellar reviews. The most notable example right now, of course, is the long-rumored “Snyder Cut” of Justice League.

There are three main reasons why interest in the Snyder Cut has grown in the months since speculation about its existence began: Zack Snyder’s fans have notoriously voracious appetites for anything he makes; some genre news sites love an opportunity to report on nerdy apocrypha; and—feel free to respectfully disagree—Justice League was not a great movie. The unique confluence of these factors helped create the idea that if enough people made enough noise and signed enough petitions, a Snyder Cut might be willed into existence, which could/would validate hardcore fans’ belief that Justice League was always a solid film hampered by studio interference.

Even though Snyder has a history of recutting his films like Watchmen and Sucker Punch for their home releases, the complicated circumstances surrounding Justice League’s filming and post-production made it so that that wasn’t in the cards.

Following the sudden death of his daughter, Snyder bowed out of Justice League, and Joss Whedon was given editorial and reshooting duties in order to make sure the film was delivered on time. Because of these things, there simply wasn’t a true director’s cut to be made of the film.Both Warner Bros. and Snyder himself have said as much, but the existence of shot footage and incomplete scenes that don’t fit within the larger context of the film’s narrative continues to keep Snyder Cut loyalists agitating for it.

To many, the very thought that there might be a Snyder Cut locked away in a vault somewhere is an insult to Snyder as a director and to DC’s fandom. But the fact remains that an assortment of deleted scenes being slapped onto an otherwise finished film does not a director’s cut make, or at least, it doesn’t make something that deserves being labeled as a “director’s cut.”

The explanations Snyder Cut enthusiasts give for why they’re so bullish run the gamut, from wanting to see what Justice League might have been like had Whedon never been involved in the project, to substantiating the idea that reviewers have been participating in a massive plot to tank the DCEU. The common thread throughout them all is that a Snyder Cut could effectively function as Justice League’s “second chance” in the public eye, but again—that’s not really what directors’ cuts are for.

A director’s cut is meant to act as supplementary material that enhances a movie, including things that, at one point, were shot and edited with the intention of being included in the final product before pre-release alterations were made for things like studio and MPAA approval.

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner is an excellent example of a film whose subsequent edits were in the true spirit of directors’ cuts, because the re-releases weren’t just longer—that would be an extended cut, something often conflated with a director’s cut. Rather, both Blade Runner (The Director’s Cut) from 1992 and Blade Runner (The Final Cut) from 2007 were creative collaborations between Scott, the studio, and film restoration producers to clarify and improve upon aspects of the original.

A director’s cut isn’t, or at least shouldn’t be, thought of as the “real” movie because audiences are told (through press tours and advertisements) that the movie they’re paying to see in theaters is The Movie™ as it was intended to be. Snyder is notable for releasing director’s cuts for a number of his movies, and while that’s technically fine, at some point one has to wonder why the filmmaker won’t just get into the habit of making leaner movies capable of standing on their own that he’s happy with.

Regardless of how you feel about Justice League, it’s the movie that Warner Bros. put out and millions of people flocked to theaters to see. Whether that was a good idea is certainly up for debate, but audiences should want studios to stand by the features they release and weather whatever negative responses the public has to them. In the long term, the communication that comes from that kind of push-and-pull relationship can lead to the development of popular, robust cinematic universes. But the conversations necessary to make that happen become derailed when directors’ cuts become mythic promises of what might have been that people refuse to get over and let go.

Original link : https://io9.gizmodo.com/directors-cuts-wont-save-you-1828551658